The Federal Reserve is best known for setting the Fed Funds Rate which is the interest rate that the Federal Reserve charges banks for overnight loans. That, in turn, influences, or outright directly adjusts, several other interest rates that have a meaningful impact not only on business, but American citizens and consumers as well

What Is the Fed’s Balance Sheet?

What is the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet?

Well, that’s a tiny bit complicated. To understand you have to accept the concept that there is a certain amount of money floating around in the U.S. economy at any one time. That amount is not fixed. One day, you have $50,000 in your checking account, and a $50,000 loan, for a total of $100,000 floating around in the overall money supply. The next day, you use that $50,000 in your checking account to pay off the loan, essentially removing that $50,000 from the economy.

The U.S. economy is enormous, and at any one time there are trillions of dollars floating around in the economy. However, some of that money is moving and doing something and some of it is stuck. Think of all those gold coins in Scrooge McDuck’s vault. They exist. They are part of the money supply. When Scrooge McDuck goes into Ducktown and buys a new car, those coins become money that gets spent around town. The dealership owner pays his workers. The owner and the workers buy groceries and gas and go to the movies and so on. The more money that floats around the better the town’s economy does.

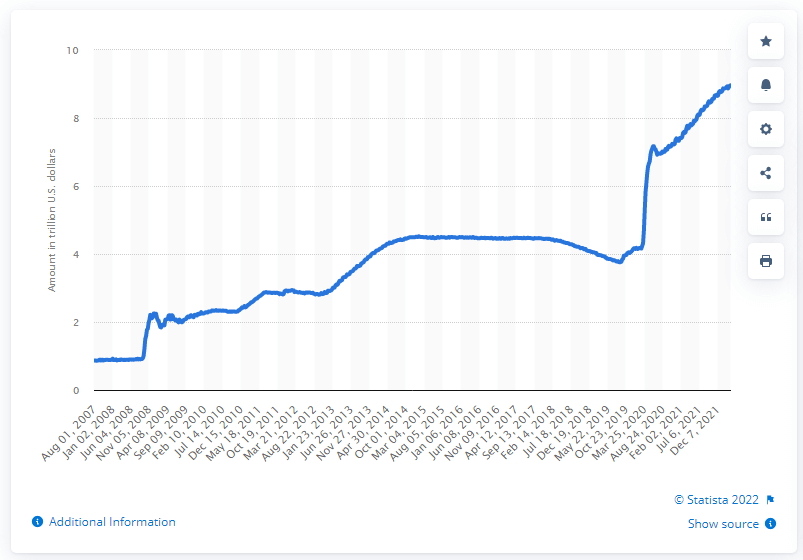

The Fed’s balance sheet works the same way except instead of a vault of coins they have rock solid credit. So, when there isn’t enough money, they dealership owner can’t pay as many workers. Those workers can’t buy as many groceries and movies and so on. To “create” new money the Fed buys US Treasuries and, in this case, mortgage-backed securities.

Buying creates money. As an oversimplified example, if Wells Fargo has $1 billion of mortgage-backed securities, it owns $1 billion, but it can’t spend that $1 billion because it is in that investment. When the buys the mortgage-backed security from Wells Fargo, then Wells Fargo has $1 billion in cash, which is can go spend (lend). Do this over and over again with staggering amount of money and you end up with a lot more cash in the economy which stimulates the economy.

Inflation and the Fed’s Balance Sheet

Today, the concern is about inflation which is caused in part by too much money. (Actually, too much access to money, but close enough) The Fed raising interest rates makes it harder to get loans and makes you use more money to pay those loans back, which effectively reduces the amount of money in the economy, thereby decreasing spending and hopefully, inflation.

But, you remember all of those securities and treasuries the Fed bought in order to put more money into the economy? They don’t just disappear into thin air. The Fed still owns all of those things. It sits there collecting the interest and principal payments which are used to pay off that credit it used to buy them in the first place. (This is all on a computer. There is no real money at the Fed.)

In some cases, the Fed can just stop buying and do nothing else. The Fed’s balance sheet will shrink as those bonds and securities are paid off. That $1 billion mortgage-backed security from Wells Fargo is receiving payments from homeowners. Depending on how the security was structured it could be paid off in a year or two. In the meantime, all of that money is leaving the money supply. $1 billion in payments that was money floating around in the economy disappears back into the Fed’s computers where it came from.

Why does this matter?

When you talk about this much money it is easy to make a mistake. Dump all of the securities back onto the market could overwhelm the system causing untold issues. So, the Fed likes just letting things “roll off” the balance sheet. In this case, it wants to reduce its balance sheet — and by extension the money supply — quicker than just letting things roll off, so it will have to sell some of its investments. It will do this slowly and publicly to ensure that there are no issues.

Ideally, the Fed’s balance sheet goes back to neutral (zero-ish if you count a certain way) before the economy cracks and they have to reverse the process. If you’re old enough to remember, the Fed tried to raise rates toward more normal interest rates before, but the housing bubble and the great recession snapped the economy in half and they had to go back to buying.

We’ll see what happens this time.